Letter to a Poet

Dear Poet,

Please accept my apologies for the delay in writing back to your wonderful question. You ask, How does a poet get better at the craft? Ah, what a question — I love that question. My ideas are like a flashlight looking for the answer, though — I only see dimly and not far. I rely so much on those poets who are wiser than I am for better light — searchlights, floodlights — the sun!

Perhaps my hero Wendell Berry says it best — he has a poem called "How to Be a Poet" — I'll include his whole poem below — but here are the first lines:

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill—more of each

than you have—inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity.

I love that Berry begins with sitting down. That was the first thought that came to mind when I read your question. Getting better at the craft rarely happens until writing becomes a discipline, truly a practice. I don't believe it has to be absolutely a daily practice, but it does have to be regular. Reliable. I sincerely believe poetry needs to be able to rely on us to be at a certain place and time and will look for us there. Discipline is a beautiful thing, and the body and mind respond to it (perhaps crankily in the beginning, but later with gratitude and even, eventually, some grace).

My second thought that came right on the heels of the first — racing to overtake it — was reading. Reading poetry widely and deeply — all sorts of poets. I know from your poems that you already do this, but I include it here because I believe that it is one of the best ways to learn and improve, one of the lasting ways. As with everything else worthwhile and good, it takes time and requires us to venture into discomfort: eras we don't care for, poets that chafe, poems that require us to stretch our minds beyond what we know, what we think we understand. I worry that if we focus largely on contemporary poetry, we miss all the wise poets from history who are still speaking to us, still so vivid and alive — poets like Dickinson, Donne, Chaucer (so funny!), Whitman, Shakespeare, Keats, and going back to the beginning, the Beowulf poet, and more and more. And oh! poets who write in other languages — so many and so vital: Issa, Neruda, Dante, Wang Wei, Kabir, Rilke, Borges, Jules Supervielle (one of my favorites), plus more and more — an ocean of poets for the mind to swim in.

My third thought is craft reading -- reading writers who are discussing their own work, or the craft of others. When my brain is too full of poems, I turn to these kind of books and read them like candy: transcripts of interviews, essays on poetry. Mary Oliver wrote A Poetry Handbook, Seamus Heaney has several books about poetry, and Annie Dillard wrote The Writing Life. The University of Michigan has a series called Poets on Poetry, and I recommend their books. It's great to read them after you've digested a poet's work for a while — you can read the essays/interviews for dessert. You probably know our fellow Oregonian William Stafford's Writing the Australian Crawl, but there are many more — Joy Harjo, A.R. Ammons, Garrett Hongo, Yusef Komunyakaa. Donald Hall is another poet who writes about poetry as well as he writes poetry itself. His book called Breakfast Served Anytime All Day is worth more than one read.

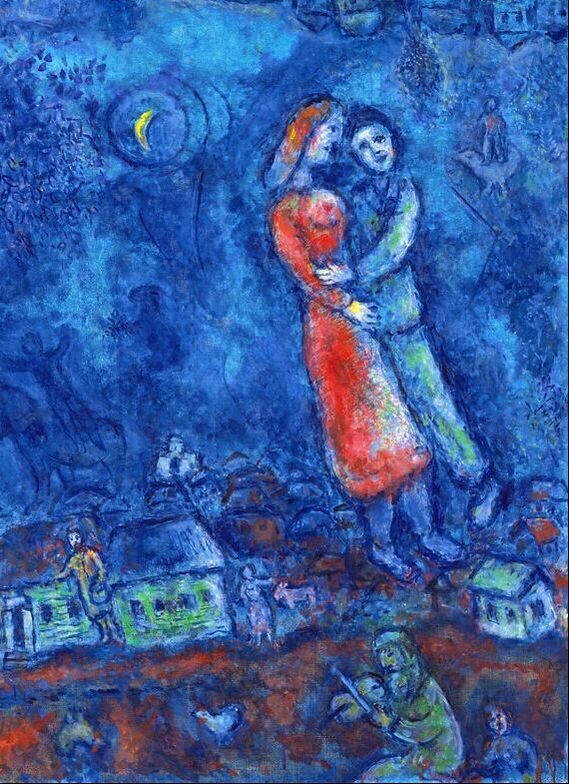

My last thought, which should have been the first, is love. Wendell Berry is right when he calls it "affection," but I think love properly covers more ground: when we understand what poetry does to us, what it gives us, how it changes our lives — we love it. And when we love it, our relationship with it deepens and grows lighter at the same time — we take it seriously, but with the seriousness of a lover: we float through the air solemnly like Chagall's lovers. There are poems I love so dearly that they have become part of my brain — sometimes they appear in my thoughts as if spoken by an inner voice. There are poets I read over and over and yet each time seems new and charged, and poets whose work I sink into as if it has always been rooted there. So yes and always, love. I suspect that you have that deeply in you already, as that was the seed that sent up the flower of your question.

Oh Poet, I hope these ideas are of some use to you. Thank you for your question, for helping me think through this beautiful craft in which we are working.

I send this with many good wishes to you and your future poems --

Warmly,

Annie

How to Be a Poet

(to remind myself)

i

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill—more of each

than you have—inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity. Any readers

who like your poems,

doubt their judgment.

ii

Breathe with unconditional breath

the unconditioned air.

Shun electric wire.

Communicate slowly. Live

a three-dimensioned life;

stay away from screens.

Stay away from anything

that obscures the place it is in.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

iii

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

~ Wendell Berry

*** With many thanks to Emmett Wheatfall, the poet who first asked me this wonderful question

Please accept my apologies for the delay in writing back to your wonderful question. You ask, How does a poet get better at the craft? Ah, what a question — I love that question. My ideas are like a flashlight looking for the answer, though — I only see dimly and not far. I rely so much on those poets who are wiser than I am for better light — searchlights, floodlights — the sun!

Perhaps my hero Wendell Berry says it best — he has a poem called "How to Be a Poet" — I'll include his whole poem below — but here are the first lines:

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill—more of each

than you have—inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity.

I love that Berry begins with sitting down. That was the first thought that came to mind when I read your question. Getting better at the craft rarely happens until writing becomes a discipline, truly a practice. I don't believe it has to be absolutely a daily practice, but it does have to be regular. Reliable. I sincerely believe poetry needs to be able to rely on us to be at a certain place and time and will look for us there. Discipline is a beautiful thing, and the body and mind respond to it (perhaps crankily in the beginning, but later with gratitude and even, eventually, some grace).

My second thought that came right on the heels of the first — racing to overtake it — was reading. Reading poetry widely and deeply — all sorts of poets. I know from your poems that you already do this, but I include it here because I believe that it is one of the best ways to learn and improve, one of the lasting ways. As with everything else worthwhile and good, it takes time and requires us to venture into discomfort: eras we don't care for, poets that chafe, poems that require us to stretch our minds beyond what we know, what we think we understand. I worry that if we focus largely on contemporary poetry, we miss all the wise poets from history who are still speaking to us, still so vivid and alive — poets like Dickinson, Donne, Chaucer (so funny!), Whitman, Shakespeare, Keats, and going back to the beginning, the Beowulf poet, and more and more. And oh! poets who write in other languages — so many and so vital: Issa, Neruda, Dante, Wang Wei, Kabir, Rilke, Borges, Jules Supervielle (one of my favorites), plus more and more — an ocean of poets for the mind to swim in.

My third thought is craft reading -- reading writers who are discussing their own work, or the craft of others. When my brain is too full of poems, I turn to these kind of books and read them like candy: transcripts of interviews, essays on poetry. Mary Oliver wrote A Poetry Handbook, Seamus Heaney has several books about poetry, and Annie Dillard wrote The Writing Life. The University of Michigan has a series called Poets on Poetry, and I recommend their books. It's great to read them after you've digested a poet's work for a while — you can read the essays/interviews for dessert. You probably know our fellow Oregonian William Stafford's Writing the Australian Crawl, but there are many more — Joy Harjo, A.R. Ammons, Garrett Hongo, Yusef Komunyakaa. Donald Hall is another poet who writes about poetry as well as he writes poetry itself. His book called Breakfast Served Anytime All Day is worth more than one read.

My last thought, which should have been the first, is love. Wendell Berry is right when he calls it "affection," but I think love properly covers more ground: when we understand what poetry does to us, what it gives us, how it changes our lives — we love it. And when we love it, our relationship with it deepens and grows lighter at the same time — we take it seriously, but with the seriousness of a lover: we float through the air solemnly like Chagall's lovers. There are poems I love so dearly that they have become part of my brain — sometimes they appear in my thoughts as if spoken by an inner voice. There are poets I read over and over and yet each time seems new and charged, and poets whose work I sink into as if it has always been rooted there. So yes and always, love. I suspect that you have that deeply in you already, as that was the seed that sent up the flower of your question.

Oh Poet, I hope these ideas are of some use to you. Thank you for your question, for helping me think through this beautiful craft in which we are working.

I send this with many good wishes to you and your future poems --

Warmly,

Annie

How to Be a Poet

(to remind myself)

i

Make a place to sit down.

Sit down. Be quiet.

You must depend upon

affection, reading, knowledge,

skill—more of each

than you have—inspiration,

work, growing older, patience,

for patience joins time

to eternity. Any readers

who like your poems,

doubt their judgment.

ii

Breathe with unconditional breath

the unconditioned air.

Shun electric wire.

Communicate slowly. Live

a three-dimensioned life;

stay away from screens.

Stay away from anything

that obscures the place it is in.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

iii

Accept what comes from silence.

Make the best you can of it.

Of the little words that come

out of the silence, like prayers

prayed back to the one who prays,

make a poem that does not disturb

the silence from which it came.

~ Wendell Berry

*** With many thanks to Emmett Wheatfall, the poet who first asked me this wonderful question